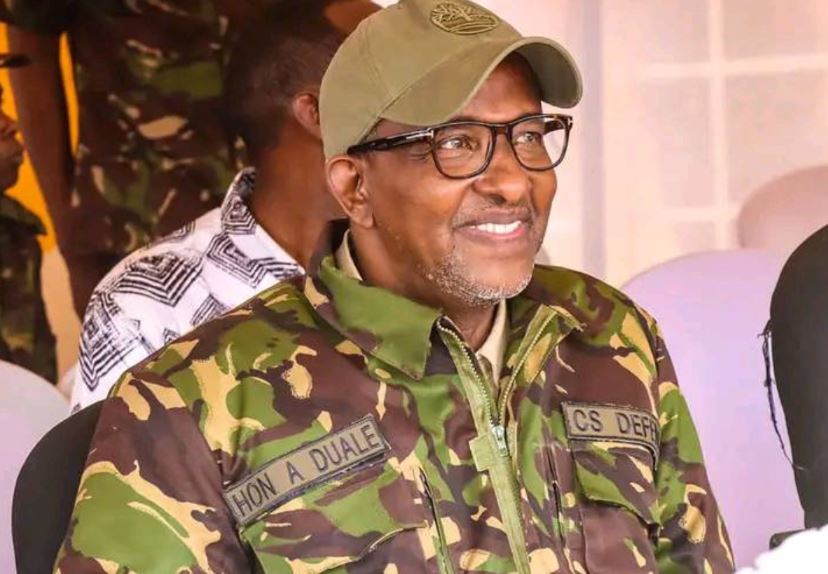

Aden Duale: How Garissa boy realised big dreams in face of adversities

His father, a polygamous pastoralist, regarded education as a waste of time and urged him to tend to the family’s camels

In the mid-1970s in Garissa’s Urgaad village, a young Aden Duale went about his routine, herding his father’s camels and spending evenings with him listening to global news from BBC and Deutsche Welle.

A decade earlier, the region had experienced the Shifta war and Duale had a first-hand experience of the brutalities visited on locals by the military. Some people he knew were killed.

More To Read

- DCI forwards 18 SHA fraud cases to ODPP with 24 suspects charged

- Government orders supermarkets, retailers to cease selling unregistered and counterfeit medicines

- Kenya urges stronger regional cooperation as transport corridors fuel disease risks across East Africa

- Garissa County launches digital livestock vaccination drive to boost pastoralist resilience

- Garissa resident sues National Assembly over police service commission appointments

- Governors sound alarm as 934 newborns die amid funding row in health sector

In the secessionist conflict, ethnic Somalis in the Northern Frontier District of Kenya, as the region was then known, had attempted to join neighbouring Somalia.

“Growing up, I just dreamt of being a lawyer, or working in foreign affairs, more so, after spending evenings with my father listening to global news media such as the BBC and DW. Was I determined to change Garissa, or even Urgaad village? It wasn’t something you dream at that early age. I wanted a better life for my family, and myself, and for everyone we went to school with,” Duale says.

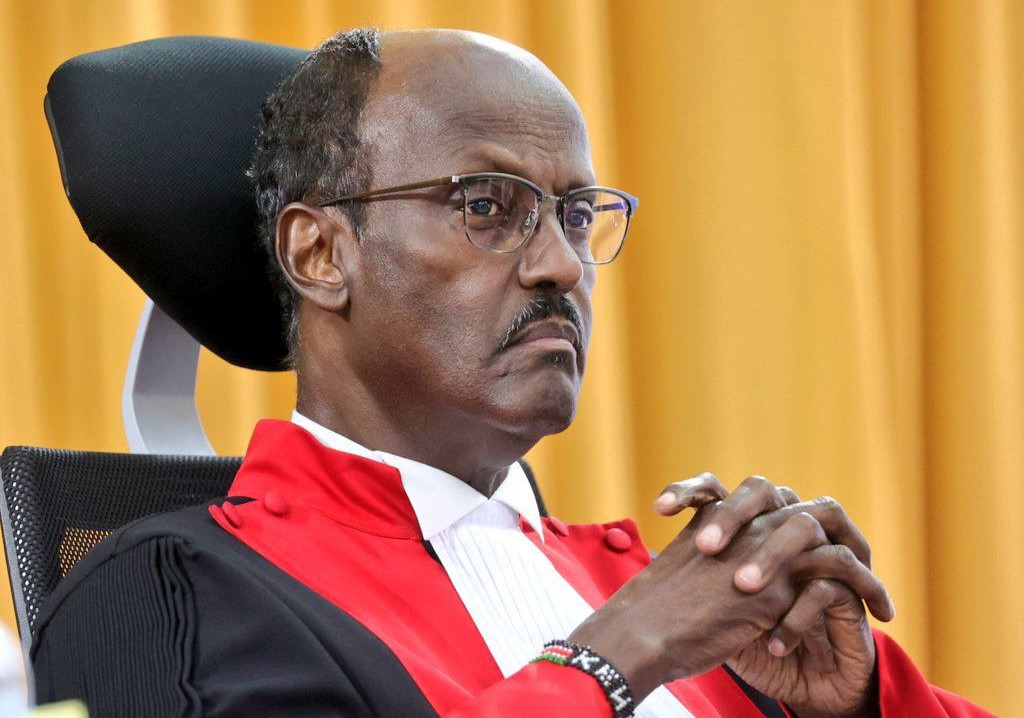

The Defence Cabinet Secretary spoke to The Eastleigh Voice about his memoir For The Record, a book he credits for the inside story of power politics, law-making and leadership in Kenya.

In the engrossing memoir, Duale skilfully transports readers from his humble beginnings, where he overcame poverty through sheer determination, to his current position as the Defence minister, solidifying his reputation as an exceptional statesman.

He displays an incredible ability to recall past events with vivid clarity. Whether it’s recounting the exact make and model of the cars he travelled in decades ago, painting a vivid picture of long-forgotten meetings, or even describing the scent of someone he sat with years ago, Duale’s descriptive prowess shines through, leaving readers captivated by his storytelling skills.

Duale’s journey from poverty to prominence is a tale of resilience and opportunity.

Raised in a family grappling with financial hardships, he was unable to afford shoes in his early years. He bravely traversed the scorching terrain of Garissa barefoot, until a well-wisher gifted him his first pair of shoes. It was not until he enrolled at Garissa High School that Duale experienced the luxury of closed shoes and sleeping on a proper bed.

“My parents did the bulk of the work to nurture my dreams. We had it rough in those early days, but they never gave up. They never lost hope. And, you know, they were pastoralists and businesspeople. They taught me how to make money, sending me to the streets of Garissa to hawk eggs from house to house,” says Duale.

Equally intriguing are the circumstances that ignited his pursuit of education. Initially believing education to be out of his reach, he harboured a deep fascination for schools and yearned to unravel the mysteries they held. His father regarded education as a waste of time and urged him to tend to the family’s camels.

His father, Mzee Barre, a polygamous pastoralist, sold merchandise and was constantly on the move.

His mother, Hawa Kosar, also played a huge role in shaping his life. Despite being a tea and porridge vendor, she was a formidable figure, and he attributes a significant portion of his success to her unwavering determination to provide for her children.

He shares the immense pain he experienced after his mother succumbed to Covid-19, and the tragic deaths of two of his brothers in a car accident.

So, why did he decide to write his book?

“The intention was simply to tell the story of my life. To inspire the children and young people across Kenya who are growing up in very difficult and challenging circumstances — that their beginnings will not determine how it all ends.”

Most importantly, he says he wanted to tell the story of the Kenyan parliament as the first Majority Leader following the promulgation of the 2010 constitution.

Duale delves into his various career choices before joining politics, starting with the military, which he abandoned after realising it was a controlled environment. He then attempted to study law but faced challenges with admission due to competitiveness.

Eventually, he pursued a degree in Education at Moi University in Eldoret and became a teacher. However, he later quit teaching and relocated to Mombasa where he excelled in business and established connections in the coastal city and in government circles.

His political ambitions emerged in the early 2000s, driven by the desire to bring fresh energy into governance and end discrimination against the Somali community in Kenya.

His initial dream to run for office in 2002 was put on hold by former military chief General Mohamud Mohamed Barrow and others.

General Mohamud had a considerable influence on Duale, and their relationship sometimes turned into political rivalry.

Duale married the General’s daughter and together they have seven children.

Interestingly, the book also highlights his victory over Farah Maalim in the highly contested Garissa town election in 2017. He considers it a significant achievement given Farah’s political background as Kenya’s former Deputy Speaker of Parliament.

Although he has defeated several other candidates in elections, he chooses to focus primarily on his win against Farah, repeatedly using the word “floored” to highlight this particular victory.

Duale also talks of his firing as Majority Leader in the National Assembly.

“The week before I was fired, Ruto's inner circle tested the waters, claiming that there was Jubilee Asili, the authentic Jubilee, and even branded some offices which Ruto opened. The slogan changed slightly from ‘Tuko Pamoja’ used by Jubilee to ‘Sote Pamoja’.”

“As expected, Jubilee quickly rushed to the Registrar of Political Parties to block the registration of the new party. It was a diversion, and they fell into the trap. As they focused on making sure no new party was registered, we quietly worked to get our house in order,” Duale says.

Duale believes the future is bright for northern Kenya residents, especially the Somali community, who have faced harassment when seeking national identity cards.

The government recently abolished the mandatory vetting for IDs in Isiolo, Marsabit, Mandera, Wajir, Garissa and Tana River which was introduced following the Shifta insurgency.

Before you go, how about joining our vibrant TikTok and YouTube communities for exciting video stories?

Top Stories Today